Like (almost) everything in human history, Quality has also evolved over time – from an ancient concept based on inspection by the end consumer to modern approaches with strategic focus. To learn more about this “prehistoric quality” – spanning from the hunter-gatherer era to the pre-Industrial Revolution period – click here.

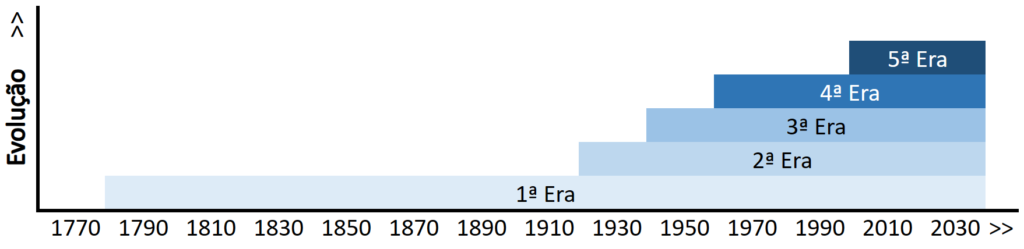

The evolution of quality prior to the Industrial Revolution can be observed through historical records and evidence from various peoples and regions of the world. More recent developments in quality—starting from the 18th century—were defined by professor and economist David A. Garvin (2002), who organized this evolution into four distinct periods known as “The Four Eras of Quality.”

Below is a summary of the modern “Eras of Quality,” according to Garvin:

1st Era: The Era of Inspection

(Pre-Industrial Period to Late 19th Century)

Development of measurement systems and standards for attribute control

With the Industrial Revolution and the rise of mass production, dedicated inspectors emerged at the end of the production line, conducting (often manual) inspections on all or most of the output. Measurement systems, gauges, fixtures, and machines for interchangeable parts were introduced to achieve greater uniformity in the final result.

Quality was understood as conformity to basic standards or to (often implicit) customer expectations—and the approach was essentially reactive: action was taken only after a problem (defect) had already occurred. There was no focus on defect prevention during the process or on systematic control of raw material quality. As a result, rework and waste levels were high.

2nd Era: The Era of Statistical Quality Control (1920–1940)

Controlled quality, statistical control, and process focus

The increasing volume of production made 100% inspection costly, time-consuming, and prone to errors—leading to the emergence of statistical tools such as Shewhart’s control charts (he also created the “PDCA Cycle”) to monitor process variability and identify causes of problems during manufacturing.

Sampling inspection, based on statistical principles, became common practice, replacing full inspection; intermediate checkpoints were added throughout the production process for continuous monitoring. The new techniques allowed not only for monitoring and evaluation but also for data-based suggestions to improve quality.

At this stage, quality came to be defined as conformance to technical specifications, with a strong focus on reducing process variability. Quality was now seen as something to be controlled and ensured during manufacturing—not just passively verified at the end.

3rd Era: The Era of Quality Assurance (1950–1970)

Emergence of the value chain concept and focus on management systems

Quality evolved from a production-centered control to a broader management discipline, aiming to build and ensure quality throughout the organizational system. The emphasis on defect prevention continued but now extended from initial design to later stages. It became clear that all processes (the “value chain”) impacted the final outcome.

Documented systems and procedures were developed and implemented to ensure quality in all stages (design, engineering, procurement, production, sales, after-sales service, etc.), and quality audits were introduced to verify conformity and effectiveness. Important concepts and tools also emerged and gained strength, such as:

- Quality cost quantification: Analyzing costs associated with non-conformance (failures, rework) and investments in prevention and evaluation;

- Total Quality Control (TQC): The idea that quality is everyone’s responsibility within the organization;

- Reliability Engineering: Ensuring that the product functions as expected over a specified time;

- Zero Defects: A movement and goal aimed at the total elimination of errors and defects.

Thinkers such as Deming and Juran had a profound influence, especially in post-war Japan’s industrial reconstruction (through Juran, quality came to be defined as “fitness for use”—meaning the product or service should meet customer needs and expectations).

It became clear that quality involved multiple departments and was not just a production function. Thus, the main objective now was to ensure that the entire organizational system could consistently and reliably deliver products and services with the desired quality.

4th Era: The Era of Strategic Quality Management (1970/1980–Present)

From desire to satisfaction; quality as strategy

Quality transcends the production function and becomes a central competitive business strategy. The focus shifts to customer satisfaction (or delight), continuous improvement of all processes, and recognizing that quality is everyone’s responsibility. Moving beyond the limitations of previous approaches (such as the narrow focus on “defect-free” products), an outward-looking view is adopted, aiming to understand customer needs and benchmark against competitors.

The pursuit of excellence is driven by the implementation of a comprehensive management philosophy like TQM, which integrates all levels and functions of the company—from top leadership to the front lines. Senior management demonstrates a strong commitment to quality, while employees are empowered and engaged at all levels. Strategic partnerships with suppliers are also developed, and tools and methodologies like the PDCA Cycle, Kaizen, Six Sigma, Lean Manufacturing, and benchmarking are used with a focus on continuous improvement.

Emphasis is placed on results-oriented process management, and the adoption of quality management system standards like ISO 9000 enables the systematization and auditing of quality practices. These methods and approaches are fundamental in creating a quality-focused organizational culture and ensuring the long-term sustainability and competitiveness of the company.

The Future: The “5th Era” or “Quality 4.0”

Lean/Toyota, strategic vision, and Industry 4.0 data

As anticipated by scholars like Garvin (who defined the previous four eras), the evolution of quality does not stop. We are now entering a new phase, driven by technological advances. This “5th Era” or “Quality 4.0” integrates consolidated learnings (such as from Lean and the Toyota Production System) with the capabilities of Industry 4.0. The focus expands toward an even more strategic vision, encompassing the customer’s holistic experience (CX) throughout their journey and emphasizing organizational agility and resilience.

In Industry 4.0, technologies such as Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT) are used to monitor, predict, and control quality in real time. These tools enable the automation of inspections and decisions, as well as continuous process optimization based on data. Mass personalization also stands out, allowing the creation of products and services tailored to individual customer needs, while co-creation involves customers directly in developing and improving solutions.

Additionally, the intelligent use of data supports more efficient risk management, anticipating and mitigating operational and market issues. Agile methodologies are applied to accelerate improvement cycles and foster greater adaptability to change. In this context, quality is understood as the value perceived by the customer throughout their entire experience with the brand, emphasizing the organization’s ability to rapidly adapt to market changes and new expectations.

Incremental Evolution

It is crucial to understand that each new era does not replace but builds upon and adapts the principles of previous ones—a cumulative evolution. Tools and concepts like inspection, statistical control, and management systems remain relevant, even if they are now applied in new ways or specific contexts (such as 100% inspection currently used in software development processes, where every line of code is reviewed before progressing through the development flow).

With this in mind, the most appropriate graphic representation of the evolution of Quality across eras is one that shows:

Self-Evolution

Quality, as a discipline, has the fundamental purpose of driving continuous improvement in any area where it is applied—industry, services, commerce, healthcare, and beyond. And in order to achieve its goals successfully, the discipline of Quality itself demonstrates a remarkable ability to self-evolve, continuously refining its methods—whether through the creation of new concepts or the reinterpretation of existing ones.

In a way, Quality practices what it preaches: continuous improvement—even of itself, in a cyclical process much like the PDCA Cycle itself.